Much of what Project Adventure is, and hopes to achieve, is reflected in the delivery of it’s experiential training workshops, and the relationships it has formed within the adventure education community.

Project Adventure is much more than just the name of the organisation – it is a unique approach to education which places an emphasis on having fun to help people learn. Fun is a major element because, in our experience, people learn more effectively if they enjoy what they are doing.

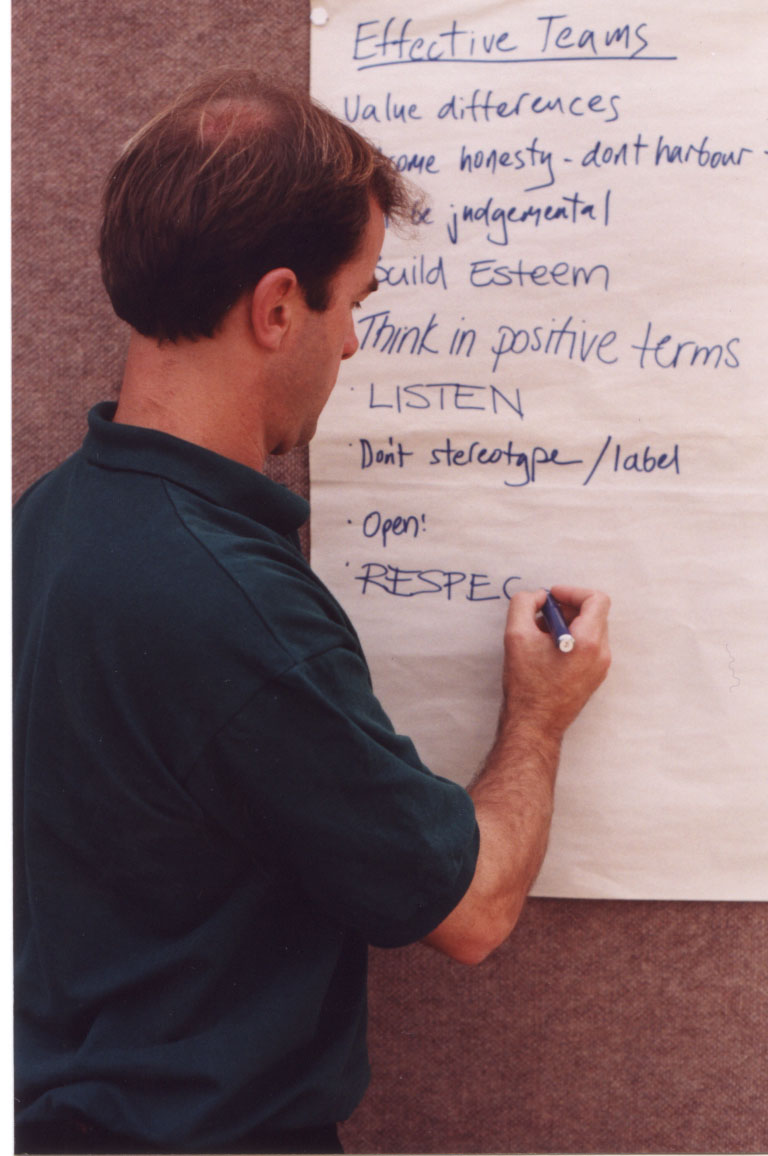

Much of the rationale for an “adventure approach” to education and recreation is found in the positive outcomes that result from people simply trying the various activities we present. There are, however, several important learning goals which every Project Adventure program aims to achieve. They are to:

• Increase participant’s sense of self-esteem and confidence

• Increase mutual support and cooperation within the group

• Value differences within a group

• Experience success and have fun

Project Adventure programs are characterised by an atmosphere that is fun, supportive and challenging. Supported by this positive environment, people are challenged to go beyond their self-perceived boundaries and learn more about themselves, and their colleagues.

A term coined by Karl Rohnke many years ago – a good idea doesn’t care who it belongs to – sums up a lot of what Project Adventure is on about. This approach – or philosophy – permeates every training program, and more broadly, the relationships it builds with clients and participants.

Key Philosophies Project Adventure applies a simple, yet powerful approach to programming that is characterised by five key philosophies:

• Challenge by Choice

• FUNN (Functional Understanding Not Necessary)

• Sequencing

• Full Value Contract

• Experiential Learning Cycle

Challenge by Choice

This means you give participants the choice to determine their level of involvement (or challenge) in a given activity. Nobody is forced to do anything they don’t want to do. The motivation to participate comes from within, rather than from external influences.

However, “challenge by choice” is more than simply saying “No”, and pulling out of the activity. It’s about creating a safe learning environment for participants which helps them make appropriate decisions in an atmosphere of care and support. In essence, the aim is to empower participants to make their own decisions, and take responsibility for their actions, but also encourage them to “give it a go”.

A choice not to participate in a particular activity – or (more often) to assume a role that is more comfortable for the participant – is always respected. Real success and learning occurs only when individuals choose and commit to their own standards and goals that are personally meaningful.

FUNN

Obvious fun is very hard to stand away from, and so the FUNN (Functional Understanding Not Necessary) element of a program goes a long way towards involving everyone’s participation. Karl Rohnke – author of many Project Adventure titles – coined this term, and it it’s an absolute gem. Applied liberally throughout your program, it says “if it’s fun, I want to be a part of it”.

FUNN means that it’s okay to be involved in an activity for no other purpose than to enjoy it. Facilitators, or the participants, do not need to have a special reason to do an activity. Do it for the laughs, the play and the good feelings it creates. The results of FUNN are surprising. Indeed, it is possible to know a person better through five minutes of play than in a week of deep conversation. Project Adventure takes fun more seriously!

Sequencing

While there is no magic formula that can help achieve the perfect program, often the key to success is the sequence of a program’s activities.

Sequencing involves making the order of a program’s activities appropriate to the needs of the group. This means preparing the group, both physically and emotionally, for the tasks ahead of it. This is a not a new concept, but one that applies across the Project Adventure curriculum regardless of the content.

The use of “lead-up” activities is critical. Without appropriate lead-up, a facilitator may jump into activities for which the participants are not ready. For example, the use of a few introductory or “ice-breaker” activities, which develop focus and allow people to “let off some steam” will often create a more positive and productive atmosphere. Or perhaps, the activities are designed to highlight a particular learning outcome of the session.

Sequencing also relates to the necessary adjustments that are made when a facilitator leads adventure activities. Because the PA activities elicit a range of behaviours, feelings and attitudes, observations of what is going on with a specific group is an equally important key to sequencing. No two groups are the same. Just because there are similar characteristics does not mean that each group should not be treated individually.

It’s like “learning to crawl before you walk”. Appropriate sequencing helps participants achieve success, but it will also help create a positive learning experience for all.

Full Value Contract

Effective learning occurs in an environment where what is learned can be put into practice and the learner can receive accurate feedback and reinforcement. Experiential learning is particularly effective in encouraging and supporting individuals who are developing new approaches and behaviours in their lives.

In Project Adventure’s experience, the Full Value Contract is an effective device that helps frame a group’s experience, and stimulates learning by helping group members to achieve their goals in a safe learning environment. Basically, the “contract” is a statement (written or oral) made by each group member concerning what he or she is willing to do during the group experience. Its primary purpose is to help group members define what areas of learning they want to explore, what behaviours are acceptable, and perhaps those they wish to change.

The “contract” can be presented in many different ways, from the subtle to the very formal, and is often developed by the group reaching consensus on their group objectives. In its original format, the Full Value Contract asks for the following four commitments:

• An agreement to work together to achieve individual and group goals;

• An agreement to adhere to certain safety and group behaviour guidelines;

• An agreement to give and receive honest feedback; and

• An agreement to give other group members and ‘self’ full value for their ideas and efforts (that is, to not devalue others or self).

Experiential Learning Cycle

The experiential learning cycle is the foundation of all Project Adventure programs. It suggests that the transfer of learning will be more effective if what is being learned is discovered though actual experience; or, as it is sometimes referred to, as “learning by doing”.

However, simply engaging a group in a series of activities one after the other will not automatically effect learning. If the program goal is to use a series of activities to enhance learning, the program leader will need to facilitate the learning process – or in other words, process or debrief the group’s experience.

Processing the Learning Experience

You may have heard the phrase “let the mountains speak for themselves”. It suggests that anything that a group may learn from an adventure experience will happen of its own accord. Well, this philosophy may work for those who heard the message. But what about those who didn’t, or perhaps, heard the wrong message? They risk leaving the program without gaining any value from it, or worse, receiving a negative experience.

Conducting a “debrief” (review of an activity) provides an opportunity for members of the group to come forth with their own perceptions of “what it all means”. Guided by the questions of a facilitator, participants can talk things out and tackle relevant issues, such as communication and leadership within the group. They can also provide feedback to one another and raise significant learning points.

Volumes have been written on the art and science of processing a group experience. It seems that many program leaders have difficulty with this part of the activity. This may perhaps be because it is so important, or that a lot of people make a big deal out of it. The following discussion describes a simple three-step model developed by Project Adventure to give facilitators a few pointers.

‘What, So What, Now What?’ model

Just as the activities in a program need to be sequenced, a facilitator should also sequence the group’s discussion. Ease into a debrief by beginning with the facts. Ask “what?” type questions to start with. This will get people talking. If appropriate, the discussion will then move onto the next step – interpreting what happened.

Some examples of “what?” type questions may include “What did the group do next when the second beach ball was introduced?”, “What methods were used by the group to solve the problem?” and “How did the group come to a decision?”

The next step presupposes that we do something with what we hear. To find out what this all means, ask “so what?” type questions. At this point it is important to ask questions that help the group find its own answers. This is a good place in which to address issues such as trust, communication, safety, leadership and co-operation. These “so what” type questions may ask “What made the method of solving this problem so effective?”, “Why did the group become frustrated with this activity?”, or “How did it feel to be left out of the decision making process?”

The most powerful step is moving the group on to consider “now what?” A standard type question to ask is “What have we learned in this activity that we can apply back at school (or work or other setting)?” Sometimes, these connections are very clear, while other times the group has no idea.

Use questions that help your participants see the big picture. Other examples include “Give me an example of how we could improve our co-operation based on what we have learned from this activity”, or “What goals can we set for this group to improve your overall performance?”